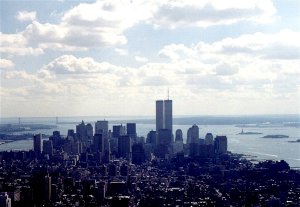

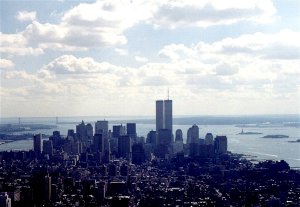

On Sept. 11 last year, up to 1 million people were evacuated from Lower

Manhattan by water "in an emergent network of private and publicly owned

watercraft--a previously unplanned activity." It was an American Dunkirk,

like the epic rescue of the British army at Dunkirk in 1940 by an armada of

similar craft.

Yet you most likely never saw this astonishing event, reported last month by

Professor Kathleen Tierney at the annual meeting of the American

Sociological Association, on television and never read about it in the print

media. It would have made for spectacular TV imagery; yet, as an example of

calm and sensible and spontaneous action, it did not fit the media image of

panic, an image that will doubtless be re-enacted next week.

Tierney, director of the Disaster Research Center at the University of

Delaware, argued that the reaction of people at the World Trade Center was

what one might have expected from the research literature of the last 50

years on behavior in disaster situations. ''Social bonds remained intact and

the sense of responsibility to others--family members, friends, fellow

workers, neighbors and even total strangers remains strong. . . . People

sought information from one another, made inquiries and spoke with loved

ones via cell phones, engaged in collective decision-making and helped one

another to safety. When the towers were evacuated, the evacuation was

carried out in a calm and orderly manner.''

There is growing research literature that Tierney cites that leaves little

doubt about this description. (See also Lee Clarke's article in the current

issue of the new sociological journal Contexts.) Many will not believe that

the scenario could possibly be true. Doesn't everyone know that there is

panic in disaster situations? Don't people become frightened, selfish and

flee in headlong panic?

The answer is no, they don't. The proof that this was not true on Sept. 11

is to be found in the fact that 90 percent of the people in the World Trade

Center escaped--which would have been impossible had people panicked. Most

people are cool under such pressure. Their old social networks do not

dissolve, and new social networks emerge. The paradigm of humankind as a mob

simply isn't true. We are social animals, and even when terribly frightened

we remain social animals.

Note that most of the positive social behavior that saved so many lives was

not organized by any formal agency, much less by any command-and-control

mechanism. People saved themselves. Other people converged from all over the

city to help. As Tierney says, "The response to the Sept. 11 tragedy was so

effective precisely because it was not centrally directed and controlled.

Instead it was flexible, adaptive and focused on handling problems as they

emerged."

In some sense, Sept. 11 was a victory over the terrorists. Socially

responsible free Americans prevented the loss from being much worse. Yet,

the response of the planning agencies has been to establish more and more

elaborate command-and-control structures, which will force a population that

is not about to panic into panic behavior.

Says Tierney: "When Sept. 11 demonstrated the enormous resilience in our

civil society, why is disaster response now being characterized in

militaristic terms?"

Perhaps because those who are determined to control everything don't

understand that even in military situations, it's the second lieutenants and

the sergeants who win battles, as, for example, in the Omaha Beach chaos at

Normandy.

Generals sitting in faraway bunkers cannot control battles. Neither can

bureaucrats far from the scene of tragedy, no matter how elaborate their

plans.

The media got the story all wrong because the panic paradigm is still

pervasive and because no one in the media had read the disaster-research

literature. They thus reinforced the propensity of those running the country

not to trust the good sense and social concern of ordinary folk. Rather,

they want to control everything with such ditsy ideas as the proposed

Homeland Security Department. That plan would take union and civil service

protections away from government workers and accomplish little else.

You can count on it: In the orgy of self-pity in which the media will engage

next week, no one will pay any attention to why there was no panic in the

evacuation, much less to the American Dunkirk at the lower end of Manhattan.

Nor will anyone argue that the only kind of formal plan that will work in

similar situations is one that is sensitive to and ready to integrate with

the powerful social propensity of the human species.